ADAPTATION AND OVERLOAD:

THE CORNERSTONE TO SUCCESSFUL TRAINING.

What you need to know...

In general terms, adaptation is your body’s reaction to a stimulus. That stimulus can be from many sources, such as a type or intensity of training. For example – if you begin to incorporate more high intensity efforts regularly within your training, it’s likely that over time you would start to create a better tolerance to the build up of lactate within your muscles.

That’s the sensation of burning when you’re working hard on a climb, or indeed sprinting with your mates to the coffee shop at the end (or in my case half way through) a ride. The output is that you can either work at a much higher intensity for the same duration, or a bit higher intensity for a longer duration. In the gym, an example of increasing intensity would be lifting progressively heavier weights over time, or the same weight for more repetitions. It’s the same principle.

Adaptation covers everything from the immediate effects of starting to pedal, right the way through to the continued effects of a phase of structured training. What your body does to deal with these changes is quite remarkable. From increasing your heart rate and breathing rate, or increasing the rate of energy turnover in your cells, to increasing the density of blood vessels in your muscles and the carrying capacity of your blood (more red blood cells).

Your body is continually assessing your needs and making little changes in order to optimise the process. A bit like the workflow of a business. If something is not needed (such as you stop training), a response is generated (you reduce blood volume and in time, heart size). The result is you either get better at it (by doing it more) or worse at it (by doing less). The gym equivalent of this would be better co-ordination of the exercise (from nerves sending better signals so the muscles) or bigger muscle fibers being used to move the weight.

But to make positive changes to your body, and therefore improve your training, a consistent effort has to be made in order to reach a new ‘normal’. You may see the term ‘homeostasis’ used with regards to this. All that means is that your body is continually trying to deal with stresses on your systems in order to return it to a resting state.

Your training will alter your resting state, making you more efficient. For example, tracking your average heart rate at rest or during a session will likely show a decrease over time. This is because you have developed a bigger heart and more efficient transport system. Therefore less beats are required for the same amount of oxygen delivery. At the elite end of our sport, pro’s often have a resting heart rate in the low 40’s during the season. (Check out a youtube video from GCN and EF Education’s Whoop Bands for more info).

Overload should go hand in hand with adaptation – if training is to be effective. Overload is what happens when you apply a stimulus to the body above what it is accustomed to. The reason that it’s important to your improvement is because we need to track it in order to ensure that we apply just enough to improve, and not too much to cause issues. A bit like the Goldilocks principle – get it just right!

Overload is concerned with the magnitude (or size) of training load. In order for improvements to be made, we need to ensure that it’s above your habitual level. For example, if you want to ride a century, you’ll probably increase the distance you ride each week leading up to the event. This is known as progressive overload.

Let’s say you can already ride a century, your overload comes by increasing the speed at which you complete it. You would overload via intensity of effort in order to improve your time. Within the gym scenario, once a weight becomes easy to lift, you need to increase the weight to continue to cause improvements.

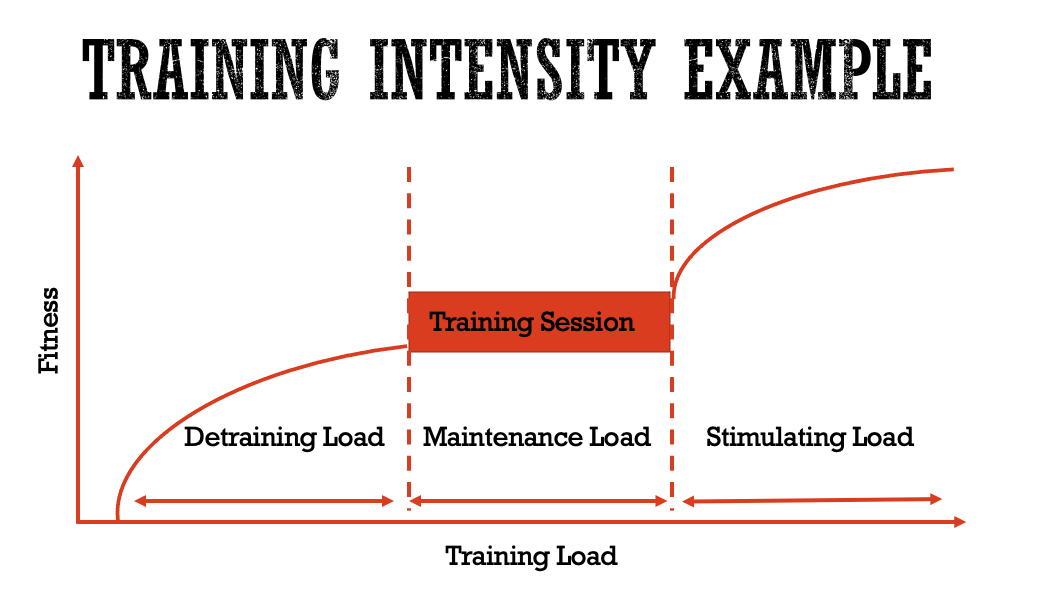

The below diagram hopefully helps to explain this. It shows what can happen to your fitness if you train at different intensities. Lowering intensity (distance, watt output, or weight lifted) will cause a detraining effect over time (you can no longer lift the weight you once could), doing the same training intensity will cause a maintenance effect (you’ll maintain fitness), and increasing the intensity will cause an improvement in fitness.

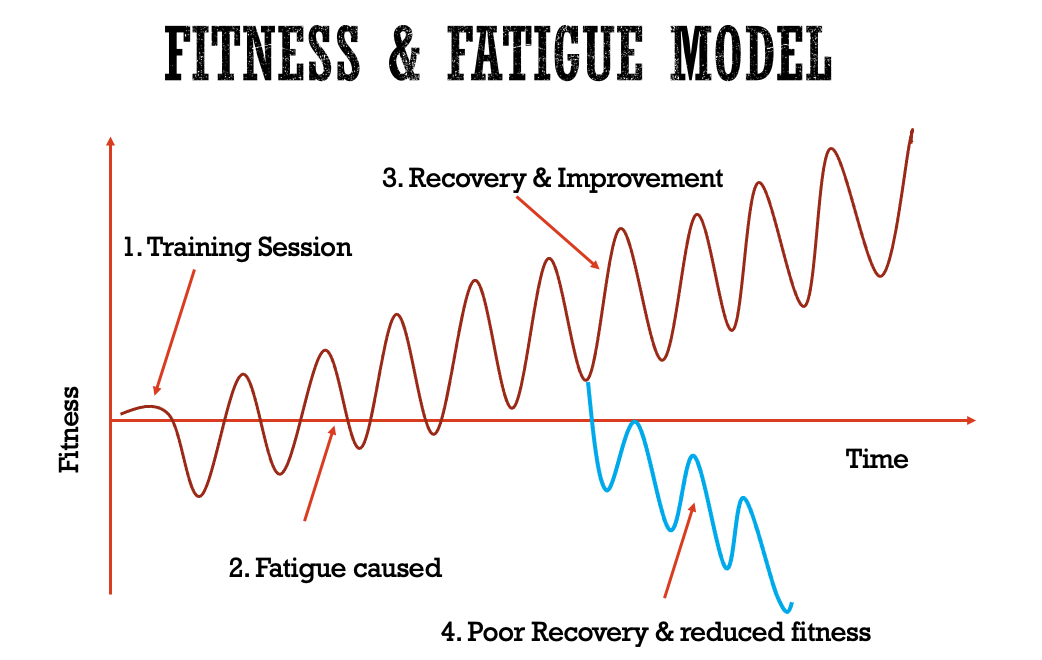

By stringing a number of sessions together in the right way, we can cause a consistent improvement in performance, seen below in the red line. Each peak is a training session (1), followed immediately by the downward line (2. Fatigue). As our body adapts to the training, we can push it harder causing the red line to push upwards, causing improved performance.

However, a lack of recovery, or sessions that are too intense close together could lead to reduced performance, seen in the blue line (4).

Now we know that increasing intensity is important, how do we measure increasing intensity (overload) and as a result adaptation? To answer that, we need to know the context in which we are measuring. For instance, is it on-bike or off-bike. Before we get into weight training methods, on bike formats that you might be more familiar with would include the distance covered, the height gained, the time spent in particular heart rate or power zones.

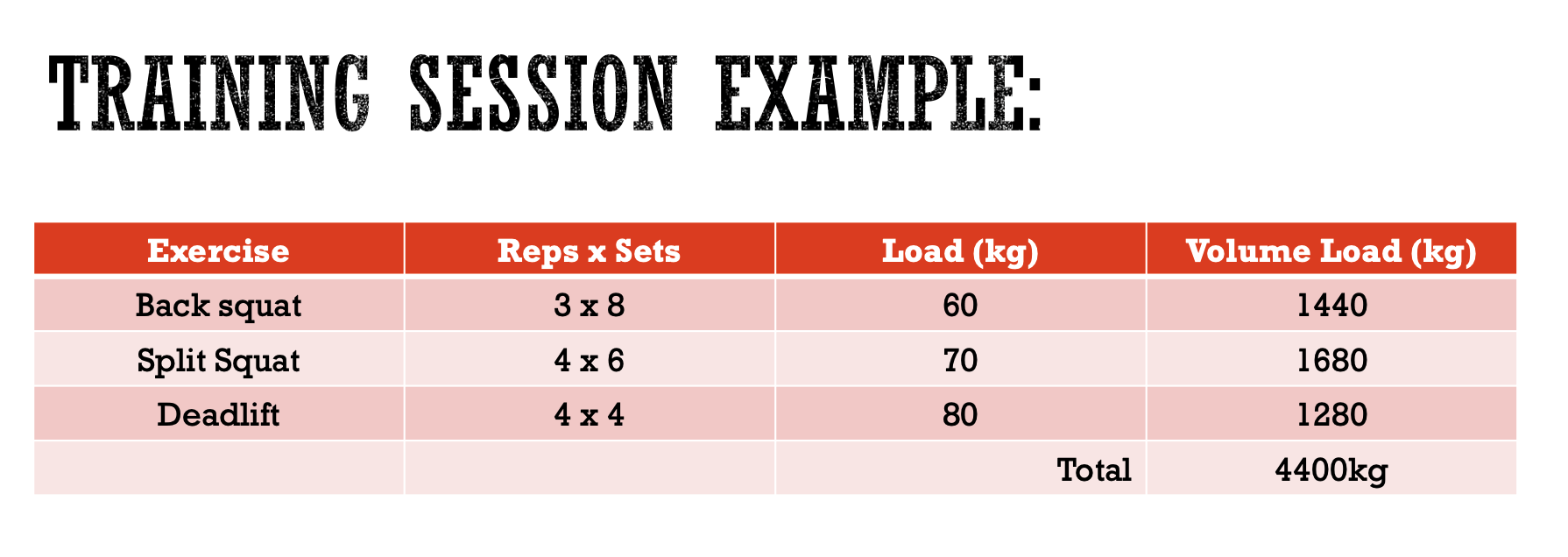

For weighted exercise, that involves measuring the load lifted. This is known as the tonnage. There are a number of ways in which this can be calculated, however, the basic method is to multiply the repetitions, the sets and the load lifted. The result will be the tonnage for the training session.

Here’s an example of a training session and the calculation of tonnage:

As you can see, it can be easily worked out per session. By tracking this over time, it is possible to see progression – similar to increasing distance, or time spend it training zones on the bike.

Here’s the important point with tracking tonnage:

This is where most people make the first weight training mistake… In order to track tonnage using this format, you need to keep the exercises the same within the training sessions. Because different muscle groups are used in different exercises, you can’t track load if you change the exercises you’re using every session. Create a plan and stick to it. By all means, try new stuff, but the nucleus of your programme should remain the same for that phase of training.

For example, if you plan on completing two weight sessions per week (we’ll cover more on this in another post), keep the same 3-4 exercises within those sessions. Outside of this is known as ‘assistance’ exercises. That’s where you have play time and figure out new exercises to use and which one’s you don’t like. This can be within the warm-up, or the rest period of your main exercise list.

Once your weight training is trackable, it can inform you of how you’re progressing (or not progressing, as the case may be). Then we can use it as a tool to make decisions with a justified basis.

In the next post, we’ll explore when to change the exercises….

~ JC