ACCOMMODATION: LEARN HOW AND

WHEN TO ADAPT YOUR TRAINING PROGRAMME

Are things getting a little too easy?

Now that we understand the principles of adaptation and overload, we can now look at how and when to change our programme to get the best results.

The saying ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ should be applied here. Over my time as a strength coach, I’ve seen hundreds of programmes from students. When they start out, one similarity between them is that they try to include every exercise that they have ever seen…. Maybe this it to show their knowledge of exercises, or possibly because they think greater variety leads to greater results. In any case, don’t get carried away with making it look flashy, make it usable.

Here’s some examples of why an exercise should be changed:

1. The athlete doesn’t like it

2. The athlete still can’t perform it safely, following coaching (range of motion/previous injury issues/not strong enough in certain areas etc…)

3. Facility/equipment changes force an adaptation to programming

4. The athlete is no longer getting performance improvements from that exercise

The first three are issues that occur during training that have to be dealt with time to time. However let’s explore point 4 in more detail. As we train at a specific intensity or use a specific exercise for a period of time the effectiveness of it reduces. To give you an example, think about how you felt after your first espresso… Probably ready to conquer the Stelvio Pass.

But do you still get the same effect now as you did then? Maybe it’s a little reduced – or maybe you have 2-3 espresso’s before you get the same feeling. This is because your body has adjusted to the effects of the caffeine.

Turning our attention to weight training, when a new movement pattern is introduced, the nervous system learns which muscles to activate and when (known as recruitment and rate coding). To begin with, it’s common to notice large jumps in the weight that can be lifted, or the number of repetitions completed.

This is the brain learning how to generate more force from available muscle. As training progresses and the load being lifted gets towards a maximum, increases slow down and rate of progression reduces. This is because the nervous system is using all available nerves and signals are being sent to the muscles as fast as possible.

An example of this would be a back squat. The first couple of weeks show large percentage jumps in weight. However, over time, those jumps get smaller and improvement becomes more difficult to achieve. This is totally normal, but it’s likely that you have ‘accommodated’ to that exercise.

In terms of the muscular system – a movement or exercise only uses a certain percentage of a muscle (known as muscle fibres), not the whole muscle. Why not? you might ask… Generally, this is because it doesn’t need to, and equally – you’re not strong enough to activate them.

Here’s the science: This is why training programmes use more than one exercise for the same muscle group. Over time, larger muscle fibres (known as Type II) and nerve fibres (alpha motor neurones) which are harder to activate become integrated into the fibres which are used within a specific exercise. This happens when a progressive load is used to fatigue the smaller muscle and nerve fibres. This causes the more muscle fibres and larger nerve fibres to be recruited for the movement. There is a ceiling to this, which is another reason that strength improvements slow down.

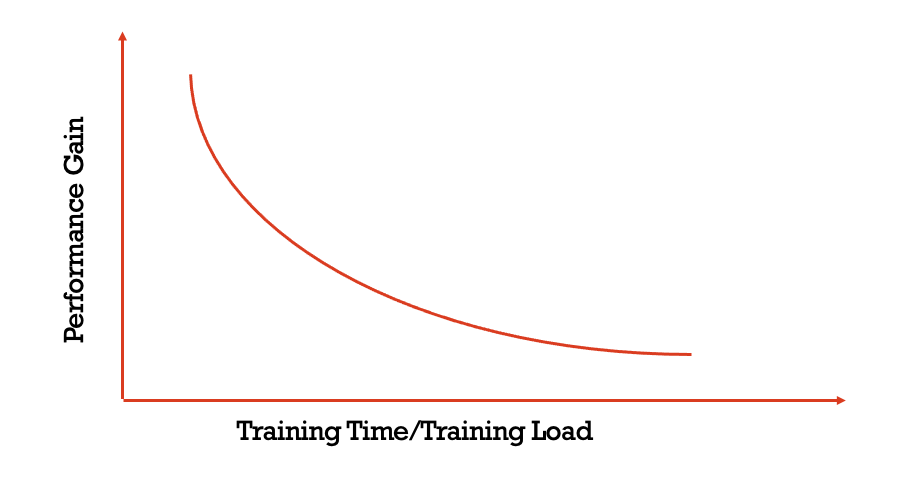

Let’s look at it in the graph below. The line indicates the performance gain over time of either an exercise, or a training programme type (so, a barbell back squat or repeated lactate efforts) or the training load used. You’ll see that it starts off going great, but reduces as more sessions are completed. That doesn't mean that you have to change the exercise all the time - it just means that you should expect a decrease over a prolonged period of time (say, 8-12 weeks).

This is totally normal and helps to indicate that a change in the programme might be in order. It's known as the Principle of Diminishing returns. This might require a subtle change such as the repetitions used, the weight lifted or a more significant change, such as with the exercise used. This could be changing from a front squat to back squat, or variations of a deadlift as examples.

Beginner athletes will have significant improvements from a change in exercise. Whilst a seasoned professional or elite athlete will still have an improvement, but it will be small in comparison.

Typically, the time period for this to occur for reps and sets is between 4-6 weeks before progressions slow. Generally this is due to your body's nerve and muscle fibres becoming used to that type of training, and have streamlined the response. So, by applying a different stimulus (heaver weights, different reps and sets, or a different duration intensity) that response will push back up on the scale.

In terms of coaching - recognising this in your athlete is important. However, acting on it at the right time is the difficult part. Change it too soon and you miss the opportunity for performance to be maximised. Change it too late and you've probably created some staleness in your athlete.

Obviously, there are other variables that will determine this time frame, such as training sessions completed, load being lifted within the phase etc. The important part to remember is that the exercise can stay the same until you’ve squeezed all the juice out of it.

So in summary – if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!

~ JC

Got a Question?

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.